The debate whether to use constructors, setters, fields, or interfaces for dependency injection is often heated and opinionated. Should you have a preference?

The argument for Constructor Injection

We had a consultant working with us reminding us to take a preference towards Constructor injection. Indeed we had a large code base using predominantly setter injection because in the past that is what the Spring community recommended.

The arguments for constructor injection goes like:

-

Dependencies are declared public, providing clarity in the wiring of Dependency Inversion,

-

Safe construction, what must be initialised must be called,

-

Immutability, fields can be declared final, and

-

Clear indication of complexity through numbers of constructor parameters.

And that Setter injection can be used when needed for cyclic dependencies, optional and re-assignable dependencies, to support multiple/complicated variations of construction, or to free up the constructor for polymorphism purposes.

Being a big fan of Inversion of Control but not overly of Dependency Injection frameworks something smelt wrong to me. Yet solely within the debate of constructor versus setter injection i don’t disagree that constructor injection has the advantage. Having been using Spring’s dependency injection through annotation a little recently and building a favouritism towards field injection I was happy to get the chance to ponder it over, to learn and to be taught new things. What was it i was missing? Is there a bigger picture?

API vs Implementation

If there is a bigger picture it has to be around the Dependency Inversion argument since this is known to be potentially complex. The point here of using constructor injection is that 1) through a public declaration and injection of dependencies we build an explicit graph showing the dependency inversion throughout the application, and 2) even if the application is wired magically by a framework such injection must still be done in the same way without the framework (eg when writing tests). The latter (2) is interesting in that the requirement on “dependency injection” is too also inverted, that the framework providing dependency injection is removed from the architectural design and becomes solely a implementation detail. But it is the graph in (1) that becomes an important facet in the following analysis.

With this dependency graph in mind what does happen when we bring into the picture a desire to distinguish between API and implementation design…

The DI graph being requested to be clarified by using constructor injection will fall into one of two categories: → ‘implementation-specific’, an interface defines the public API and the DI is held private by the constructor in the implementation class, → ‘API-specific’ when the class has no interface. Here everything public is a fully exposed api. There is no implementation-protected visibility here for injectable constructors.

By introducing the constraint of only ever using constructor based injection: in the pursuit of a clarified dependency graph; you remove or make more difficult the ability to publicly distinguish between API and Implementation design.

This distinction between API and implementation is important in being able to create the simple API. The previous blog “using the constretto configuration factory” is a co-incidental example of this. I think the work in Constretto has an excellent implementation design to it, but this particular issue raised frustrations that the API was not as simple as it could have been. Indeed: to obtain the “simplest api”; Constretto (intentionally or not) promotes the use of Spring’s injection, a loose coupling that can be compared to reflection. It may be that our usage of Constretto’s API, where we wanted to isolate groups of properties, was not what the author originally intended but this only re-enforces the need for designing the simplest possible API.

Therefore it is important to sometimes have all dependency injection completely hidden in the implementation. A clean elegant API must take precedence over a clean elegant implementation. And to achieve this one must first make that distinction between API and Implementation design.

Taking this further we can introduce the distinction between API and SPI. Here a good practice is to stick to using final classes for API and interfaces for SPI. By the same argument as above SPI can’t use constructor injection because they don’t have constructors.

Inversion-of-Control vs Dependency-Injection

What about the difference between IoC and DI. They are overlapping concepts: the subtlety between the “the contexts” and “the dependencies” rarely emphasised enough. (Java EE 6 has tried to address the distinction between contexts and dependencies at the implementation level with the CDI spec.) The difference between the two, nuanced as it may be, can help illustrate that the DI graph in any application deserves attention in multiple dimensions.

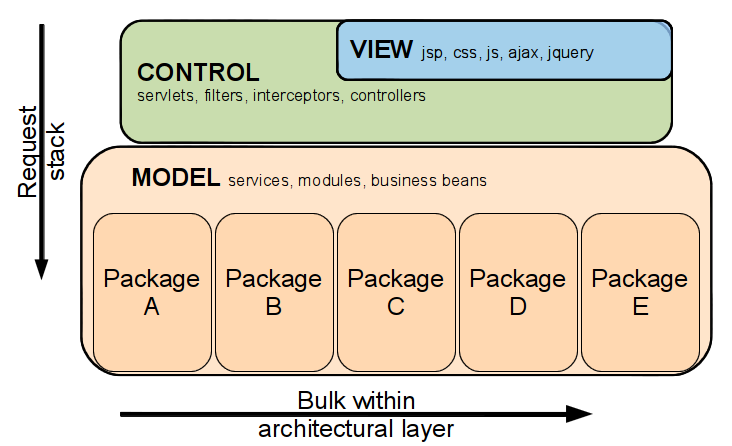

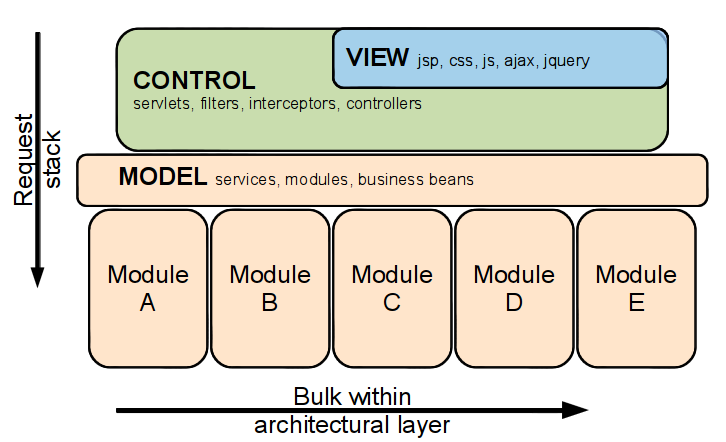

Drawing an application’s architecture up as a graph where the vertical axis represents the request stack: that which is typically categorised into architectural layers view, control, and model/services; and the horizontal axis representing the broadness of each architectural layer, then it can be demonstrated that: → IoC generally forms the passing and layering of contexts downwards.

→ The api-specific DI is fulfilling the layer of such contexts, and these contexts can be dependencies directly or helper classes holding such dependencies. Such dependencies must therefore be initially defined high up in the stack.

→ The DI that is implementation-specific is at most only visible inside each architectural layer and is the DI that is represented horizontally on the graph. Possibly still within the definition of IoC it can also be considered a “wiring of collaborating components”. The need for clarity in the dependency graph isn’t as critical and so applications here often tend towards Service Locators, Factories, and Injectable Singletons. On the other hand many of the existing Service Locator implementations have been poor enough to push people towards (and possibly it was an instigator for the initial implementations of) dependency injection.

→ Constructor injection works easily horizontally, especially when instantiation of objects is under one’s ability, but has potential hurdles when working vertically down through the graph. Sticking to constructor injection horizontally can also greatly help when the wiring of an application is difficult, by ensuring at the construction of each object dependency injection has been successful. Missing setter, field, interface injection and Service Locators may not report an error until actually used in runtime.

A simple illustration of difficulty with vertical constructor injection is looking at these helper contexts and how they may be layering contexts through delegation rather than repetitive instantiation, a pattern more applicable for an application with a deep narrow graph. This exemplifies a pattern that has often relied on proxy classes.

Another illustration is when having to instantiate the initial context at the very top of the request/application stack it involves instantiating all the implementation of dependencies used in contexts down through the stack, this is when dependency inversion explodes - the case where the IoC becomes up-front and explicit, and the encapsulation of implementation is lost through an unnecessary leak of abstractions. A problem paralleling to this is trying to apply checked exceptions up through the request stack: one answer is that we need different checked exceptions per architectural layer (another answer is anchored exceptions). With dependencies we would eventuate with requiring different dependency types per architectural layer and this could lead to dependencies types from inner domains needing to be declared from the outer domains. Here we can instead declare resource loaders in the initial context and then letting each architectural layer build from scratch its own context with dependencies constructed from configuration. But this comes the full circle in coming back to a design similar to a service locator. Something similar has happened with annotations in that by bringing Convention over Configuration to DI what was once loose wiring with xml has become the magic of the convention and begins too to resemble the service locator or naming lookups.

For a legacy application this likely becomes all too much: the declaring of all dependencies required throughout all these contexts; and so relying on a little louse-coupling-magic (be it reflection or spring injection) is our answer out. Indeed this seems to be one of the reasons spring dependency injection was introduced into FINN. And so we’ve become less worried about the type of injection used…

Broad vs Deep Applications

FINN.no is generally a broad application with a shallow contextual stack. Here is the traditional view-control-model design and the services inside the model layer typically interact directly with the data stores and maybe interact with one or two peer services.

Focusing on the interfaces to the services we see there is a huge amount of public api available to the controller layer and very little in defined contexts except a few parameters, or maybe the whole parameter map, and the current user object. There is therefore very little inversion of control in our contexts, it is often just parameterisation. (Why we often use interfaces to define service APIs is interesting since we usually have no intention for client code to be supplying their own implementations, it is definitely not SPIs that are being published. Such interfaces are used as a poor-man’s simplification of the API declaration of public methods within the final classes. Albeit these interfaces do make it easy to make stubs and mocks for tests.)

In this design the implementation details of service-layer dependencies is rarely passed down through contexts but rather hard baked into the application. And in a product like FINN it probably always will be hard baked in. Hard baked here doesn’t mean it can’t be changed or mocked for testing, but that it is not a dynamic component, it is not contextual, and so does not belong in the architectural design of the application.

In such a broad architectural layer i can see two problems in trying to obtain a perfect DI graph:

→ cyclic dependencies: bad but forgiven when existing as peers within a group. In this case constructor injection fails. We can define one as the lesser or auxiliary service and fall-back to the setter/field injection just for it, but if they are real equal peers this could be a bullet-in-the-foot approach and using field injection for both with documentation might be the better approach.

→ central dependencies: these are the “core” dependencies used throughout the bulk of the services, the database connection, resource loaders, etc. If we enforce these to be injected via constructors then we in turn are enforcing a global-store of them. Such a global store would typically be implemented as a factory or singleton. Then what is the point of injection? Worse yet is that this could encourage us to start passing the spring application context around through all our services. A service locator may better serve our purpose…

Hopefully by now you’ve guessed that we really should be more interested in modularisation of the code. Breaking up this very broad services layer into appropriate groups is an easier and more productive first step to take. And during this task we have found discovering and visualising the DI graph is not the problem. Untangling it is. Constructor injection can be used to prevent these tangles, but so can tools like maven reporting and sonar. This shows the the DI graph is actually more easily visualised through the class’s import statements than through constructor parameters.

With modularisation we can minimise contexts, isolate dependency chains, publish contextual inversion of control into APIs, declare interface-injection for SPIs, and move dependency injection into wired constructors.

Back to Constructor injection

So it’s true that constructor injection goes beyond just DI in being able to provide some IoC. But it alone can not satisfy Inversion of Control in any application unless you are willing to overlook API and SPI design. DI is not a subset or union of IoC: it has uses horizontally and in loose-coupling configuration; and IoC is not a subset or union of DI: to insinuate such would mean IoC can only be implemented using spring beans leading to an application of only spring beans and singletons. In the latter case IoC will often become forgotten outside the application’s realm of DI.

Constructor injection is especially valid when it’s desired for code to be used via both spring-injection and manual injection, and it does make test code more natural java code. But imagine manually injecting every spring bean in a oversized legacy broad-stack application using constructor injection without the spring framework - is this really a possibility, let’s be serious? What you would likely end up with is one massive factory with initialisation code constructing all services instead of the spring xml, and looking up using this factory every request. What’s the point here? This isn’t where IoC is supposed to take us.

If code is being moved towards a distributed and modular architecture you should pay be aware on how it clashes with the DI fan club.

If code is in development and you are uncertain if the dependency should be obtained through a service locator or declared public giving dependency inversion, and in the spirit of lean think it smart to not yet make the decision, then using field injection can be the practical solution.

And just maybe you are not looking to push the Dependency Inversion out into the API and because you think of Spring’s ApplicationContext (or BeanFactory) as your application’s Service Locator, you use field injection as a method to automate service locator lookups.

For the majority of developers for the majority of the time you will be writing new code, not caring about dependency injection trashing inversion of control, wanting lots of easy to write tests, and not be worrying about API design so it’s ok to have a healthy preference towards constructor injection…

Keep questioning everything… …by remaining focused on what is required from the code at hand we can be pragmatic in a world full of rules and recommendations. This isn’t about laziness or permitting poor code, but about being the idealist: the person that knows the middle way between the pragmatist and ideologue. By knowing: when what can, and for how long, be dropped; we can incrementally evolve complex code towards a modular design in a sensible, sustainable, and practical way. In turn this means the programmer gets the chance to catch breath and remember paramount to their work is the people: those that will develop against the design and those end-users of the product.

References:

-

Martin Fowler gives a great introduction into all this at martinfowler.com/articles/injection.html.

-

Taking taking this further Jaroslav Tulach presents an interesting view on Dependency Injection in relations to API design at wiki.apidesign.org/index.php?title=Dependency_Injection

-

Another read that investigates IoC : Constructor Injection vs Setter Injection - Shaun Smith

-

What’s the difference between Dependency Injection and Inversion of Control

Credits: A large and healthy dose of credit must go to Kaare Nilsen for being a sparring partner in the discussion that lead up to this article.

Tags: API Design constretto Dependency Injection Inversion of Control Legacy Systems spring Systems