In the previous article we introduced our own introduction into the world of Big Data, and explored what it meant for FINN. Here we’ll go into the technical depth about the implementation of our Big Data needs.

rehashing the previous article

FINN is a busy site, the busiest in Norway, and we display over 80 million ad pages each day. Back when it was around 50 million views per day, the old system responsible for collecting statistics was performing up to a thousand database writes per second during peak traffic. Like a lot of web applications we had a modern scalable presentation and logic tier based upon ten tomcat servers but just one not-so-scalable monster database sitting in the data tier. The procedure responsible for writing to the statistics table in the relational database was our biggest thorn. It had indeed gotten so bad that: during peak traffic; operations had to at the first sign of trouble turn off this database procedure – that is when users were getting the most traffic to their ads we had to stop collecting their statistics.

At this time we were also in the process of modularising the FINN web application. The time was right to turn our statistics system into something modern and modular. We wanted an asynchronous, fault-tolerance, linearly scaling, and durable solution.

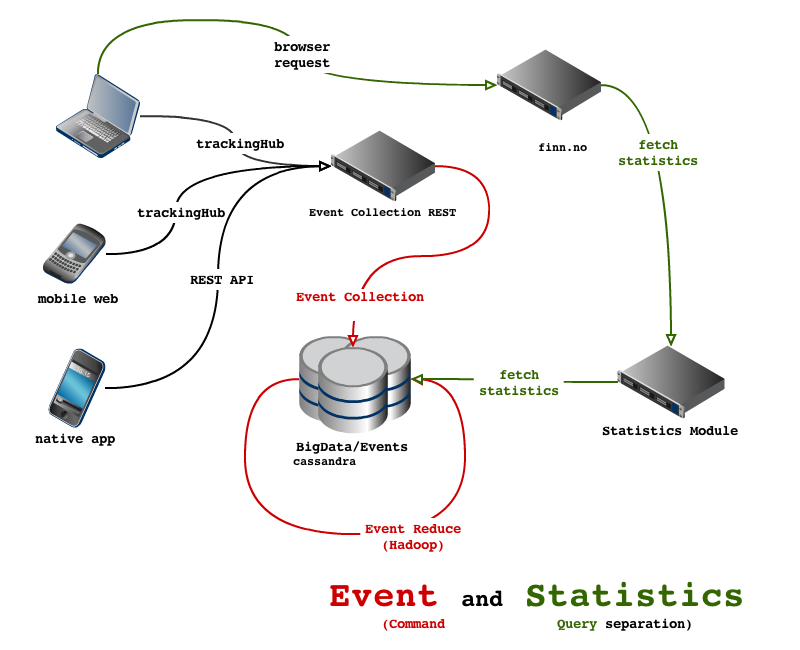

the design

The new design uses the Command Query Separation pattern by using two separate modules: one for the collecting of events and one for displaying statistics. The event collecting system achieves asynchronousity, scalability, and durability by using Scribe. The backend persistence and statistics module achieves all goals by using Cassandra and Thrift. As an extension of the push-on-change model: the event collection stores denormalised data and it is later aggregated and normalised to the views the statistics module requires; we use MapReduce jobs within a Hadoop cluster.

the statistics module

At FINN all our modular architecture is built either upon REST or interfaces defined by Apache Thrift. We discourage direct database access from any front-end application. So our Statistics module simply exposes the aggregated read-optimised data out of cassandra, with a Thrift IDL like:

service AdViewingsService {

/** returns total viewings for a given adId */

long fetchTotal(1: i64 adId)

/** returns a list of viewings for the intervals between startTimestamp and endTimestamp **/

list<long> fetchRolled(1: i64 adId, 2: Interval interval, 3: i64 startTimestamp, 4: i64 endTimestamp)

}

enum Interval { YEAR, MONTH, DAY, HOUR, QUARTER_HOUR }the event collection module

The collecting of events we wanted to happen asynchronously and in a fail-over safe manner so we chose a combination of thrift and Scribe from Facebook. Each event object, or bean, is a thrift defined object, and these are serialised using thrift into Base64 encoded strings and transported through the network via Scribe. The event collection module is nothing more than a Scribe sink and it dumps these Thrift event beans directly into Cassandra.

Each event is schemaless in its values field, it’s up to the application to decide what data to record, and is defined by Thrift like:

struct Event {

/** different categories generally won't be mixed in the normalised views. */

1: required string category;

2: required string subcategory;

3: required map<string,string> values;

}For the persistence of events in Cassandra we store events in rows based on minute by minute buckets. The partition key goes a little further and looks like <minute-bucket>_<random-number>. The reason for the additional column random_number, named “partition” in the CQL (Cassandra Query Language) schema, is it ensures write and read load is distributed around the cluster at all times, rather than one node being a hotspot for any given minute. Then each event is stored within a clustering key “collected_timestamp”. The value columns are essentially the category, the subcategory, and the json map keys_and_values.

CREATE TABLE events (

minute text,

partition int

type text,

collected_timestamp timeuuid,

collected_minute bigint,

subcategory text,

keys_and_values text,

PRIMARY KEY ((minute, partition), type, collected_timestamp)

);

CREATE INDEX collected_minuteIndex ON events (collected_minute);We have moved the category column in as the first clustering key since the aggregation jobs typically only scan one type of category at a time. In hindsight we might not have done this as it would be better to be able to use the DateTieredCompactionStrategy. Within this schema there are two timestamp that we have to work with, both the real_timestamp representing when the event happened and the collected_timestamp when the event got stored in Cassandra. Analytical jobs, like “how many bicycles were sold in Oslo on a specific day?”, are interested in the real_timestamp. While the incremental aggregation jobs are interested in aggregating just those events that have come into the system since the last incremental run.

the technologies

![]() Cassandra is truly amazing and refreshingly modern database: linear scalability, decentralised, elastic, fault-tolerant, durable; with a rich datamodel that provides often superior approaches to joins, grouping, and ordering than traditional sql. The Scribe sink simply stores the Thrift event objects directly into Cassandra. After that we use Apache Hadoop to then in the background aggregate this denormalised data. The storing of denormalised data in this manner extends the push-on-change model, an approach far more scalable “in comparison with pull-on-demand model where data is stored normalized and combined by queries on demand – the classical relational approach”1. In hadoop our aggregation jobs piece-wise over time scan over the denormalised data, normalising in this case by each ad’s unique identifier, this normalised summation for each ad is then added to a separate table in Cassandra which uses counter columns and is optimised for query performance.

Cassandra is truly amazing and refreshingly modern database: linear scalability, decentralised, elastic, fault-tolerant, durable; with a rich datamodel that provides often superior approaches to joins, grouping, and ordering than traditional sql. The Scribe sink simply stores the Thrift event objects directly into Cassandra. After that we use Apache Hadoop to then in the background aggregate this denormalised data. The storing of denormalised data in this manner extends the push-on-change model, an approach far more scalable “in comparison with pull-on-demand model where data is stored normalized and combined by queries on demand – the classical relational approach”1. In hadoop our aggregation jobs piece-wise over time scan over the denormalised data, normalising in this case by each ad’s unique identifier, this normalised summation for each ad is then added to a separate table in Cassandra which uses counter columns and is optimised for query performance.

Many of these incremental aggregation jobs could have been tackled with Spark streaming or Storm today. But 4 years ago when we started this project none of these technologies would have been capable of keeping up with our demands. Even today we’re happy that we have this system as our underlying base design, since there’s always aggregation jobs that can’t be solved with, or better solved with, streaming solutions. Having the raw events stored provides us a greater flexibility and a parallel to partition-tolerance when streaming solutions fail.

Even today we’re happy that we have this system as our underlying base design, since there’s always aggregation jobs that can’t be solved with, or better solved with, streaming solutions. Having the raw events stored provides us a greater flexibility and a parallel to partition-tolerance when streaming solutions fail.

Painting a wonderful picture, hopefully you can see it puts us one foot into an entirely new world of opportunity, but it would be a lie not to say the journey here has also come with its fair share of pain and anguish. The four key technologies we adopted here: Cassandra, Hadoop, Scribe, and Thrift; involve changes in the way we code and design.

Cassandra, being a noSQL database, or “Not only SQL”, takes some investing in to understand how datamodels are designed to suit queries instead of writes. We also been bitten by an unfortunate bug or two along the way. The first was immediately after the 1.0 release when compression was introduced and before we had a CQL schema and were storing serialised thrift events spearately in individual rows. With the compression we jumped on it a little too quickly, also modifying its default settings for chunk_length_kb to suit out skinny rows for the denormalised data. This hit a bug leading to excessive memory usage bringing Cassandra nodes down. The Cassandra community was very quickly to the rescue and we were running again with hours. The second bug was again related to skinny rows. Each of our count objects were stored in individual rows resulting in a column family with billions of rows stored on each physical machine. This eventually blew up in our face and the fix was to disable bloom filters. It’s obvious to us now that skinny rows should be avoided, and you’ll see in the CQL schema presented above that it isn’t how we do it anymore.

Hadoop is a beast of a monster, and despite bringing functional programming to a world of its own (don’t go thinking you are anything special because you’re tinkering around with Scala) in many ways much of the joy Cassandra gave us was undermined by having to understand what the heck was going on sometimes in Hadoop.  We were also using Hadoop in a slightly unusual way trying to run small incremental jobs on it with as high frequency as possible. In fact it could be that we have the fastest Hadoop cluster in the world with our set up of a purely volatile HDFS filesystem built solely with SSDs. We’ve also had plenty of headaches due to Hadoop’s centralised setup. Our Cassandra and Hadoop nodes co-existed on the same servers in the one cluster, providing data-locality – a key ingredient to good Hadoop performance. But these servers came with a faulty raid controller locking up the servers many times each day for over a year, it took HP over a year to “look” into the problem. For our Cassandra cluster it successfully proved how rock solid fault-tolerance it really has – just imagine the crisis to the company if your monster relational database was crashing from faulty hardware twice a day. But one of these faulty server was running the hadoop masters: namenode and jobtracker; so aggregation jobs were frequently crashing. Since then we’re moved these services to a small separate virtual server, together they use no more than 600mb memory.

We were also using Hadoop in a slightly unusual way trying to run small incremental jobs on it with as high frequency as possible. In fact it could be that we have the fastest Hadoop cluster in the world with our set up of a purely volatile HDFS filesystem built solely with SSDs. We’ve also had plenty of headaches due to Hadoop’s centralised setup. Our Cassandra and Hadoop nodes co-existed on the same servers in the one cluster, providing data-locality – a key ingredient to good Hadoop performance. But these servers came with a faulty raid controller locking up the servers many times each day for over a year, it took HP over a year to “look” into the problem. For our Cassandra cluster it successfully proved how rock solid fault-tolerance it really has – just imagine the crisis to the company if your monster relational database was crashing from faulty hardware twice a day. But one of these faulty server was running the hadoop masters: namenode and jobtracker; so aggregation jobs were frequently crashing. Since then we’re moved these services to a small separate virtual server, together they use no more than 600mb memory.

Using Thrift throughout our modular platform we’d already broken the camel’s back on it. But Scribe has given us plenty of problems. Like most code open sourced from Facebook it seems to be “code thrown over the wall”. It contains traces of private Facebook code, has very little logging+documentation+support, and has settings that rarely work without peculiar and exact combinations with other settings. We believed scribe to be fault tolerant when it simply wasn’t and we lost many eventsc when resending buffers after a downtime or pause period. We have since moved to Kafka, as our general messaging bus for all event driven design throughout our microservices platform.

These problems have all since been addressed – they are but part of our story. Dealing with each new technology on its own was no big deal but a strong recommendation in hindsight is not to trial multiple new technologies in the one project. The reputation of that project could well fall to that of its weakest link.

a bright prosperous future

Of all these technologies it is Cassandra that has proved the most successful, and today is the essential and fundamental technology to our “big data” capabiilities.

On top of this platform we’ve come a long way. Today we use predeominantly Spark over Hadoop, with Spark jobs submitted to our YARN cluster. Although more and more use-cases are only requiring Cassandra. Some of these examples are messaging inboxes for each user, storing users search history, fraud detection, mapping probabilities of ipaddresses to geographical locations, and providing collaborative filtering using Spark’s ALS algorithm.

Tags: Big Data Cassandra Hadoop Thrift Scribe Kafka