Some context

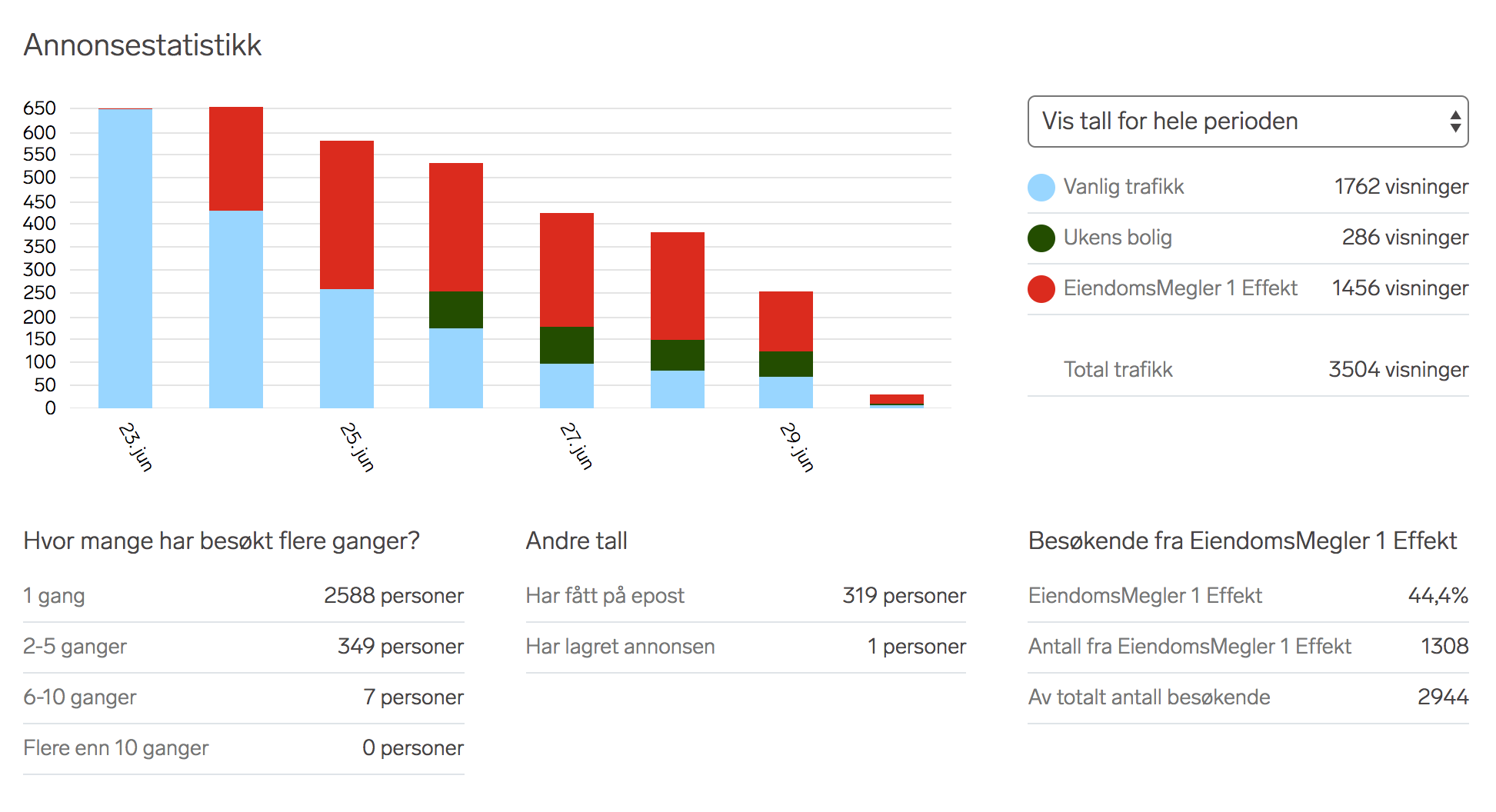

People who publish their classified ads on FINN.no get access to various statistics to see how their ads are performing. For a user it can look something like this:

The top left bar chart shows the repartition of the incoming traffic by day and the legend to the right of it shows the total numbers for each type of incoming traffic. The lower section is divided in 3 parts:

- the left part shows the number of views by unique users;

- the one to the center shows how many users have been notified of the ad by email and how many added the ad to their favorites;

- the right part shows how many viewers out of the total come from a specific type of traffic.

This gives the user basic insight into the reach of their ad, such as how many views it has and how many unique users have viewed it.

Around November 2016 there was a request to show more detailed information about the viewers, such as the age, gender and location distribution of the viewers (demographic information) so the owner could potentially change an ad to better fit the audience they wanted.

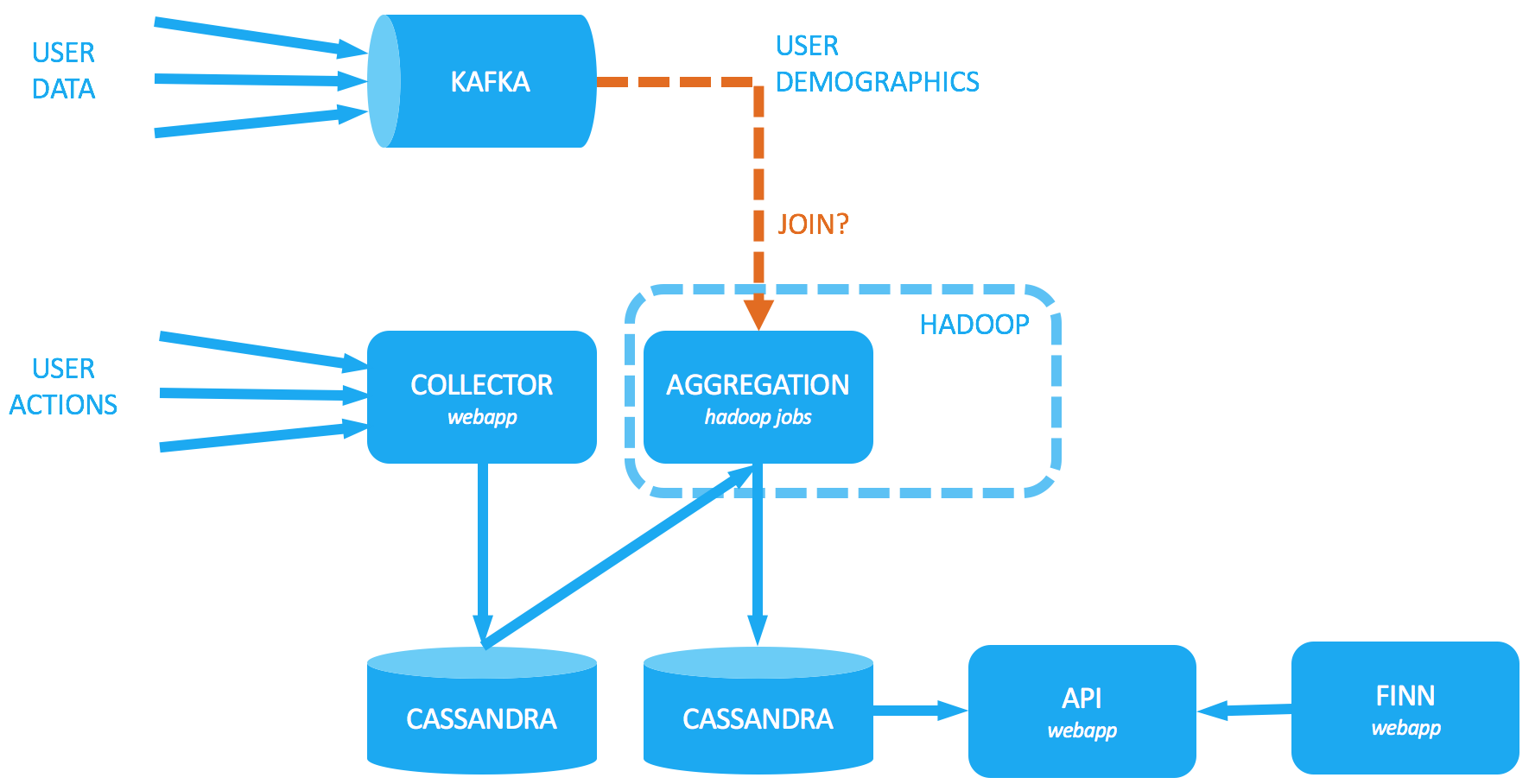

Existing solution

As users view ads, do actions (such as send a message to an ad’s owner or scroll down and read the whole page, for example), these actions are gathered and published internally on Apache Kafka. These streams of data then become the basis for computing the statistics above. The plan was then to also publish demographic data about the viewers (such as location, age and gender) on Kafka and join the user actions with this demographic data to provide enhanced statistics.

At the time, the action events published on Kafka were saved to Cassandra Apache Cassandra clusters, and statistics were being computed as batches on an aging Apache Hadoop cluster reading from Cassandra. Both our Hadoop and Cassandra clusters had not receive much love recently and were all on end-of-life versions. The old system also had an increasing tendency to fail, so we were also in the process to decide to either spend our time to refresh/renew the old system or replace it.

Replacement solution

We first tried to find a good way of joinining the latest demographic data being received through Kafka as part of the existing statistics computation done with Hadoop. We quickly learned that efficient communication with Kafka from a Hadoop job was not easy to get right. After some experimentation we had a solution that sort of worked, but it was complicated and far from elegant.

After doing some research we started to look at the possibility of using Kafka Streams. Reading the introductory blog post - especially the “Simple is Beautiful” paragraph - it felt like Streams was just what we needed.

The most interesting aspects were:

- no more external runtime for jobs (in our case YARN/Hadoop);

- no more intermediary external storage (Cassandra);

- built-in fault tolerance;

- only POJOs running as normal Java apps;

- limiting the number of components by using Kafka for the whole solution.

This would lead to less moving parts, less maintenance and what we saw as a simpler and more elegant solution.

We also evaluated other solutions, amongst which:

- upgrade our Hadoop and Cassandra clusters;

- Apache Spark micro-batches on top of an Apache Parquet storage filled from Kafka;

- hybrid solutions with hyperloglog and other similar cardinality tricks to estimate the unique users visiting an ad.

We were already using Kafka (and it is seen as a central part of our future architecture), so Streams was deemed to be the most attractive and straight-forward solution.

Streams in use

The first prototype took less than a week to get up and running, and from there it took 6 months to develop a fully operational, properly sized version running in production on our Kubernetes container cluster.

As part of development we also wrote tools for monitoring, error handling/diagnostics, reprocessing and for migration of the existing statistics out of the old Cassandra storage and into our new storage. During this development, the original plan to join in demographics data was put on hold (for non-technical reasons) and the project turned into a more technical one: move the statistics system out of the aging Hadoop and Cassandra clusters and migrate to something that incurs less maintenance and fits better with our overall technology strategy.

Requirements

The amount of data is is reasonably large, about 100 million messages a day, and the main requirements were:

- keep the near-realtime computing of the statistics we had in the previous solution;

- be able to reprocess data up to 3 months back in time (in case of failure or bugs);

- be able to integrate late arrivals to some extent.

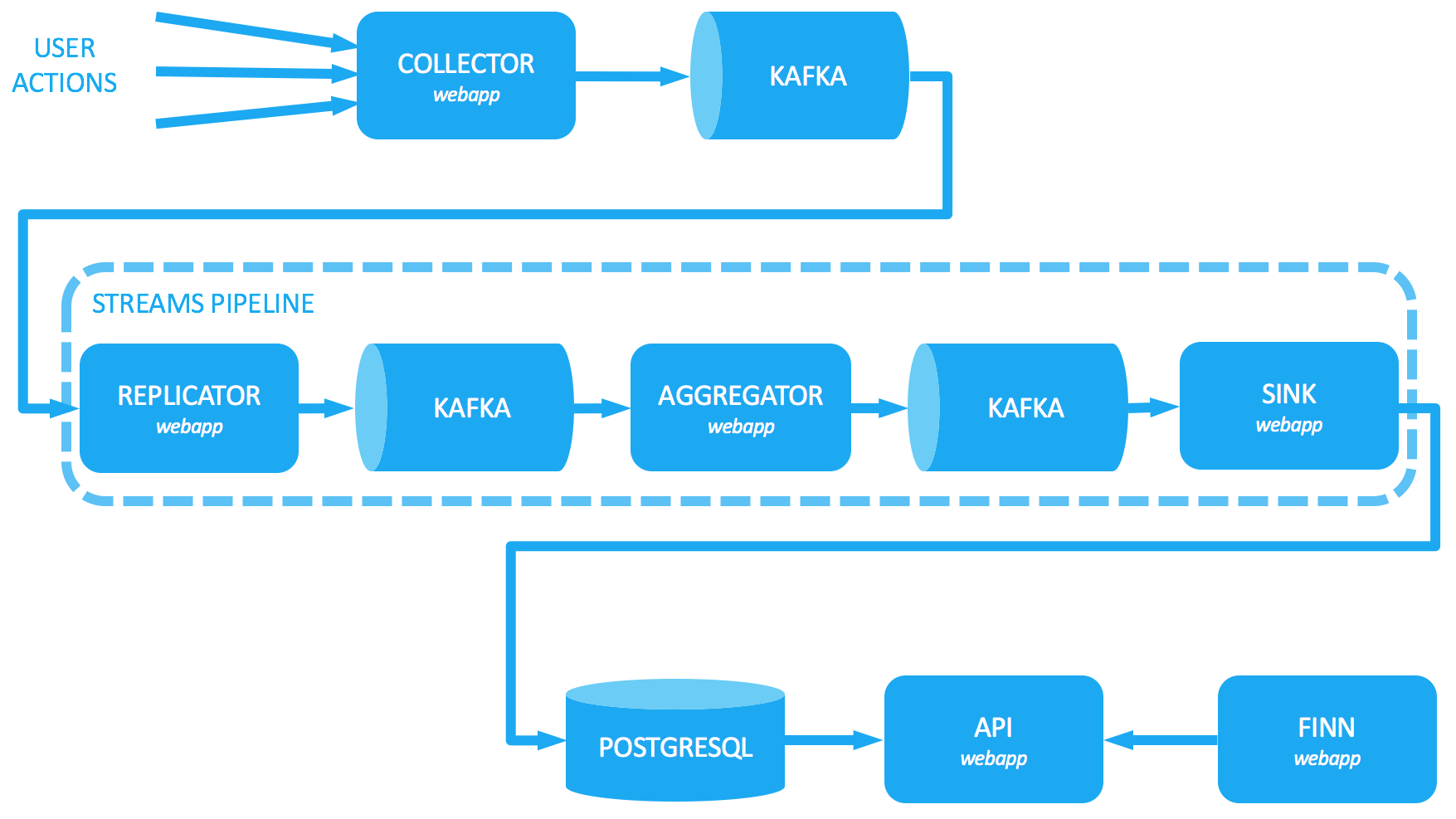

Architecture

We went through multiple versions and the components evolved both in size and responsibility during development, and below is how it looks now.

The replicator copies a subset of short lived topics (3 days retention) into our own long lived topics (90 days retention) to support reprocessing of the last 3 months. It is a simple read-write (Kafka consumer and producer) that computes the hash of the message as the key for deduplication downstream.

The aggregator is the interesting bit that actually computes the base data for our statistics: the counts. A simplified versions of the Streams code to achieve this would look something like this:

// grouping by unique key which consists

// of the id of the ad, the day the action

// happened and the type of the action

// and then counting

kstream.groupBy((key, action) -> // build the new key by which we want to count

new Key(action.ad, // ex: ad number 12345678

action.day, // ex: day 17-02-2017

action.type)) // ex: "click"

.count("count-store") // counts the number of messages for each key

.to("count-topic"); // outputs each update of the count the Kafka topic

The production code does more than that with Apache Avro serialization / deserialization, filtering of bad data, deduplicating, reporting metrics etc., but the above code shows the main logic the component consists of.

Finally, the sink is just an instance of Kafka Connect configured to use the JDBC sink - with no custom code. It reads from the output topic from the aggregator and writes into a PostgreSQL database.

All of these components are webapps running in Kubernetes and can be scaled up or down easily. And while the replicator and the aggregator are Spring Boot based webapps, the sink is just an off-the-shelf Kafka-REST webapp.

Data quality

Avro and Schema Registry

We use Avro and the Schema Registry to enforce schemas on the Kafka messages so that changes to the message structure maintain compatibility over time. This proves to be quite robust any incompatible change to the schema gets immediately rejected.

// build the serialization/deserialization object

GenericAvroSerde avroSerde =

new GenericAvroSerde(registryClient, registryProps);

// build the KStream with Avro

new KStreamBuilder()

.stream(Serdes.String(), avroSerde, topics);

A note about developing with Avro and the schema registry: While in the early stages of development, using the schema registry proved cumbersome: breaking changes happens quite often during development and maintaining compatibility or overriding it takes time to get used to. This was however very good training for applying actual real changes to the schema that will inevitably be required later on when running in production. Special care is required with the internal Streams topics that also contain Avro messages.

Streams filtering

We filter out bad messages (missing or corrupted pieces of information) with the filtering method of the Streams and plain old Java.

// filter out actions for the owner of the ad

// and actions that are missing some data

kstream.filter((key, action) ->

action.isNotFromOwner()

&& action.hasRequiredData());

Dealing with duplicates

There is no built-in support in Streams to deal with duplicates, so non-idempotent processing of the messages then becomes an issue. The strategy we adopted is to calculate a hash of each message value and set it as its key so that consumers downstream can deduplicate based on an in-memory LRU cache of these hashes (because all the identical keys are guaranteed to be in the same partition, and thus end up in the same consumer on the same thread).

In the replicator:

// compute a hash of the message and

// set it as the key

String key = DigestUtils.sha1Hex(message);

producer.send(new ProducerRecord<>(topic, key, message);

In the aggregator:

// cache processed key for 10 minutes

KEYS = CacheBuilder.newBuilder()

.maximumSize(100000L)

.expireAfterWrite(10L, TimeUnit.MINUTES)

.build();

// keep only messages whose key has not been processed

kstream.filterNot((key, action) -> {

boolean duplicate = KEYS.getIfPresent(key) != null;

KEYS.put(key);

return duplicate;

});

This is a best effort strategy since if the Streams app dies, so does its cache, and the new app instance won’t be able to deduplicate the very first duplicate (but this should happen so rarely that it is acceptable).

Limiting the disk usage

Streams and Kafka rely on offsets when reading messages which guarantees that when things start again they pick up where they stopped. On top of that, when using aggregations, Streams stores a changelog of the operations in Kafka itself, meaning that also stateful operations (grouping, reducing, counting, etc.) will recover gracefully and efficiently from a stop or crash by starting from where they had stopped. This is really nice fault-tolerance feature.

The changelog topic is used on every start to build a “local state” for stateful operations on the machine where Streams is running. RocksDB manipulates that state internally. This local state resides partly in memory and partly on disk, all depending on the amount of data in question. Instances running on our Kubernetes cluster are stateless, so they do not keep data on disk between restarts. This means we lose the local state each time the app is shutdown. However, when the streams application starts up again it will rebuild this local state from the Streams internal changelog topic, so no data is lost. As a consequence, there are two things to consider:

- rebuilding of the local state on (re)start can take several minutes depending on the volume of data and how it is partitioned

- if the app runs for a long time the disk usage will keep on increasing, so we need to use

TimeWindowsto avoid the issue of never-ending growing local state

Below is an example of how to limit data on disk by using TimeWindows.

// count by buckets of 1 day

// and keep these buckets for 1 day in the local state

.groupByKey()

.count(TimeWindows.of(TimeUnit.DAYS.toMillis(1))

.until(TimeUnit.DAYS.toMillis(1)),

"count-store");

Migrating existing data

The Cassandra table storing our data was not structured in a way that made it easy and fast to export the existing data. Since we were running on an older version of Cassandra, we used the Astyanax library to migrate the existing data over to PostgreSQL. It allowed partitioning of the ring buffer and reading in parallel from each of these partitions for higher throughput. The included checkpointing mechaninsm helped us start where it left off each time the migration would fail. Astyanax did a good job reading and writeíng the billions of rows of data needed within an acceptable migration time window without overloading the running Cassandra clusters.

The above proved to be quite tricky due to tombstone and compaction issues. Tombstones would often lead to queries timing out, so we first had to fix that. These problems were not, for the most part, visible in day to day use, so it was a surprise challenge when migrating data (which took quite a lot of time to do).

Integration testing

We use JUnit and spin up an embedded Kafka and Apache Zookeeper. Then we use producers and consumers to send and receive messages for the input and output topics that the Streams expects. Extra care should be taken to clear the state of the Streams between each test. Integration testing has proven to be quite challenging because there are a lot of details to take into account.

For manual testing when quickly prototyping something new, we both make use of our Kubernetes development environment, or a local Docker Compose configuration, and a bunch of scripts using the Kafka tools.

Reprocessing

When rolling out bug fixes or improvements, it may be necessary to reprocess the existing data. Reprocessing with Streams is sort of an artform - especially if you have non-idempotent processing. Sometimes it is possible to reset the app (with kafka-streams-application-reset) and just restart with auto.offset.reset to earliest to reprocess everything. This clears all of the app’s state, and depending on the case this can be acceptable or not.

Our aggregator can start in a special reprocessing mode that spools all the messages of our 90-days long lived topic and only processes a given time interval.

Error diagnostic

Figuring out when the Streams output data is wrong is not always as easy as seeing a sudden spike on a monitoring graph or incoherent numbers. Figuring out why the numbers do not add up can be even more challenging in that there is no way to query the input Kafka topic to investigate. The same could be said of our Cassandra “input table” to Hadoop which was not structured after a diagnostic query need either. Putting a Kafka Connect Source from our input topic to a form of storage that allows easy querying might enable easier diagnostics.

However, we’re happy to say that we never experienced any bugs in Streams itself and the Kafka cluster have proven to be very reliable. The problems we have encountered have mostly been due to corrupted or duplicated input data.

Summary

The previous solution required a lot of knowledge on top of knowing Kafka, mainly Cassandra (dealing with tombstone problems, compaction strategies, cluster management, old composite columns vs CQL etc.) and Hadoop (maintaining HDFS, operations, batch-writing etc.). Using Streams instead, there is no extra required knowledge. The only thing to know about is Kafka (and the Streams framework).

We also end up with a less heterogeneous infrastructure to run with fewer clusters and fewer products. It ends up being just one Kafka cluster and a bunch of webapps. Which we have quite a lot of experience of maintaining over time.

With Kafka being more and more widely used at FINN (as well as Streams) the knowledge can also be shared between all and promotes cooperation across the organization.

Tags: kafka streams hadoop cassandra batch