A story of getting the View layer up and running quickly in Spring…

Since the original article, parts of the code has been accepted upstream, now available as part of the Tiles-3 release, so the article has been updated — it's all even simpler!

a web application's view layer

with four simple steps using Spring and Tiles-3

to make organising large complex websites elegant with minimal of xml editing.

Contents of article… • Background • Step 0: Spring to Tiles Integration • Step 1: Wildcards • Step 2: The fallback pattern • Step 3: Definition includes • When the Composite pattern is superior • Conclusion

Background

- from a design perspective the Decorator pattern can undermine the seperation MVC intends,

- requires all possible html for a request in buffer requiring large amounts of memory

- unable to flush the response before the response is complete,

- requires more overall processing due to all the potentially included fragments,

- does not guaranteed thread safety, and

- does not provide any structure or organisation amongst jsps, making refactorings and other tricks awkward.

One of the alternatives we looked at was Apache Tiles. It follows the Composite Pattern, but within that allows one to take advantage of the Decorator pattern using a ViewPreparer. This meant it provided by default what we considered a superior design but if necessary could also do what SiteMesh was good at. It already had integration with Spring, and the way it worked it meant that once the Spring-Web controller code was executed, the Spring’s view resolver would pass the model onto Tiles letting it do the rest. This gave us a clear MVC separation and an encapsulation ensuring single thread safety within the view domain.

“Tiles has been indeed the most undervalued project in past decade. It was the most useful part of struts, but when the focus shifted away from struts, tiles was forgotten. Since then struts as been outpaced by spring and JSF, however tiles is still the easiest and most elegant way to organize a complex web site, and it works not only with struts, but with every current MVC technology.” – Nicolas Le Bas

Yet the best Tiles was going to give wasn’t realised until we started experimenting a little more…

Step 0: Spring to Tiles Integration

The first step is integrating Tiles and Spring together. For Tiles-3 it boils down to registering a ViewResolver and a TilesConfigurer in your spring-web configuration.

<bean id="viewResolver" class="org.springframework.web.servlet.view.tiles3.TilesViewResolver"/>

<bean id="tilesConfigurer" class="org.springframework.web.servlet.view.tiles3.TilesConfigurer">

<property name="tilesInitializer">

<bean class="no.finntech.control.servlet.tiles.FinnTilesInitialiser"/>

</property>

</bean> public class FinnTilesInitialiser extends AbstractTilesInitializer {

public FinnTilesInitialiser() {}

@Override

protected AbstractTilesContainerFactory createContainerFactory(TilesApplicationContext context) {

return new FinnTilesContainerFactory();

}

}Step 1: Wildcards

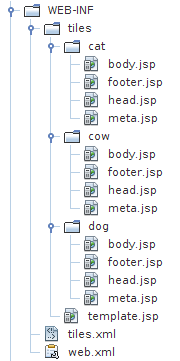

Let's declare a definition and template as below and create some files and folders as shown to the right:

//--tiles.xml

//-- anything that doesn't start with a slash is considered a definition here.

<definition name="REGEXP:([^/].*)" template="/WEB-INF/tiles/template.jsp">

<put-attribute name="meta" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/{1}/meta.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="header" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/{1}/header.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/{1}/body.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="footer" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/{1}/footer.jsp"/>

</definition>

//--template.jsp<!DOCTYPE html>

<%@ prefix="tiles" taglib uri="http://tiles.apache.org/tags-tiles" %>

<html>

<head>

<tiles:insertAttribute name="meta"/>

</head>

<body>

<div id="header"><tiles:insertAttribute name="header"/></div>

<div id="body"><tiles:insertAttribute name="body"/></div>

<div id="footer"><tiles:insertAttribute name="footer"/></div>

</body>

</html>@Controller

public class MyWebsite{

@RequestMapping("/cat")

public ModelAndView viewCat(){

Map modelMap = new HashMap();

//...

return new ModelAndView("cat", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/dog")

public ModelAndView viewDog(){

Map modelMap = new HashMap();

//...

return new ModelAndView("dog", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/cow")

public ModelAndView viewCow(){

Map modelMap = new HashMap();

//...

return new ModelAndView("cow", modelMap);

}

}The Apache Tiles tutorial on wildcards explains that to extend the use of wildcards to also allow rich regular expressions one should use the

CompleteAutoloadTilesContainerFactory. In this article we are building up our own FinnTilesInitialiser and FinnTilesContainerFactory configuration classes. To enable both wilcards and regular expressions, distinguished by the use of prefixes, we need to override the following method in FinnTilesContainerFactory…

@Override

protected <T> PatternDefinitionResolver<T> createPatternDefinitionResolver(Class<T> cls) {

PrefixedPatternDefinitionResolver<T> r = new PrefixedPatternDefinitionResolver<T>();

r.registerDefinitionPatternMatcherFactory(

"WILDCARD", new WildcardDefinitionPatternMatcherFactory());

r.registerDefinitionPatternMatcherFactory(

"REGEXP", new RegexpDefinitionPatternMatcherFactory());

return r;

}...CompatibilityDigesterDefinitionsReader cannot be cast to ...DefinitionStep 2: The fallback pattern

${options[myopts]} where "myopts" is a list-attribute that references the options in preferential order.

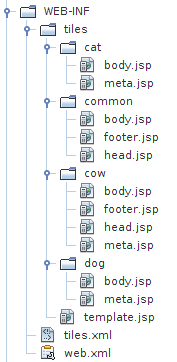

Introduce the "common" folder, as shown to the right, and the example turns into

//--tiles.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:([^/].*" template="/WEB-INF/tiles/template.jsp">

<put-attribute name="meta" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/meta.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="header" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/header.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/body.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="footer" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/footer.jsp"/>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="common"/>

</put-list-attribute>

</definition>OptionsRenderer to work in your TilesContainerFactory you'll also need to do the following

public class FinnTilesContainerFactory extends BasicTilesContainerFactory {

...

@Override

protected Renderer createTemplateAttributeRenderer(BasicRendererFactory rendererFactory, ApplicationContext applicationContext, TilesContainer container, AttributeEvaluatorFactory attributeEvaluatorFactory) {

Renderer original = super.createTemplateAttributeRenderer(rendererFactory, applicationContext, container, attributeEvaluatorFactory);

OptionsRenderer optionsRenderer = new OptionsRenderer(applicationContext, original);

return optionsRenderer;

}

....

}No more xml editing and no duplicate JSPs.

For a large company this can help enforce UI standards by having control over the common folder — keeping an eye on UI overrides and customisations never become too outlandish with the standard look of the website. The front end developer can also be referencing this common folder for UI standards.

Step 3: Definition includes

@Controller

@RequestMapping("/cat")

public class CatController{

@RequestMapping("/cat/view")

public ModelAndView viewCat(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("view.cat", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/cat/edit")

public ModelAndView editCat(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("edit.cat", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/cat/search")

public ModelAndView searchCat(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("search.cat", modelMap);

}

}

@Controller

@RequestMapping("/dog")

public class DogController{

@RequestMapping("/dog/view")

public ModelAndView viewDog(){/ /...

return new ModelAndView("view.dog", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/dog/edit")

public ModelAndView editDog(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("edit.dog", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/dog/search")

public ModelAndView searchDog(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("search.dog", modelMap);

}

}

@Controller

@RequestMapping("/cow")

public class CowController{

@RequestMapping("/cow/view")

public ModelAndView viewCow(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("view.cow", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/cow/edit")

public ModelAndView editCow(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("edit.cow", modelMap);

}

@RequestMapping("/cow/search")

public ModelAndView searchCow(){ //...

return new ModelAndView("search.cow", modelMap);

}

}//-- tiles.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:([^/.][^.]*)\.([^.]+)" template="/WEB-INF/tiles/template.jsp">

<put-attribute name="meta" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/meta.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="header" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/header.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/body.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="footer" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts]}/footer.jsp"/>

<!-- definition injection performed by DefinitionInjectingContainerFactory.instantiateDefinitionFactory(..) -->

<put-list-attribute name="definition-injection">

<add-attribute value=".category.{2}" type="string"/>

<add-attribute value=".action.{1}.{2}" type="string"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="common"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts-view" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="view"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts-edit" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="edit"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts-dog" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="dog"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts-cat" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="cat"/>

</put-list-attribute>

<put-list-attribute name="myopts-cow" cascade="true">

<add-attribute value="{2}"/>

<add-attribute value="{1}"/>

<add-attribute value="cow"/>

</put-list-attribute>

</definition>

//-- tiles-core.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:\.action\.view\.([^.]+)">

<!-- override attributes -->

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-view]}/view_body.jsp"/>

<!-- search attributes -->

<put-attribute name="view.content" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-view]}/view_content.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="view.statistics" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-view]}/view_statistics.jsp"/>

</definition>

<definition name="REGEXP:\.action\.edit\.([^.]+)">

<!-- override attributes -->

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-edit]}/edit_body.jsp"/>

<!-- edit attributes -->

<put-attribute name="edit.form" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-edit]}/edit_form.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="edit.status" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-edit]}/edit_status.jsp"/>

</definition>

<definition name="REGEXP:\.action\.search\.([^.]+)">

<!-- override attributes -->

<put-attribute name="body" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-search]}/search_body.jsp"/>

<!-- search attributes -->

<put-attribute name="search.form" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-search]}/search_form.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="search.results" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-search]}/search_results.jsp"/>

</definition>

//-- tiles-cat.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:\.category\.cat">

<!-- cat attributes -->

<put-attribute name="cat.extra_information" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-cat]}/cat_extra_information.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="cat.feline_attributes" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-cat]}/cat_feline_attributes.jsp"/>

</definition>

//-- tiles-dog.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:\.category\.dog">

<!-- cat attributes -->

<put-attribute name="dog.extra_information" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-dog]}/dog_extra_information.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="dog.k9_attributes" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-dog]}/dog_k9_attributes.jsp"/>

</definition>

//-- tiles-cow.xml

<definition name="REGEXP:\.category\.cow">

<!-- cat attributes -->

<put-attribute name="cow.extra_information" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-cow]}/cow_extra_information.jsp"/>

<put-attribute name="cow.farm" value="/WEB-INF/tiles/${options[myopts-cow]}/cow_farm.jsp"/>

</definition>public class FinnUnresolvingLocaleDefinitionsFactoryImpl extends UnresolvingLocaleDefinitionsFactory {

private static final String DEF_INJECTION = "definition-injection";

public FinnUnresolvingLocaleDefinitionsFactoryImpl() {}

// this method may return null

@Override

public Definition getDefinition(String name, TilesRequestContext tilesContext) {

Definition def = null;

// WEB-INF is a pretty clear indicator it is not a definition

if(!name.startsWith("/WEB-INF/")){

def = super.getDefinition(name, tilesContext);

if(null != def){

def = new Definition(def); // use a safe copy

Attribute defList = def.getLocalAttribute(DEF_INJECTION); // explicit injected definitions

if(null != defList && defList instanceof ListAttribute){

for(Attribute inject : (List) defList.getValue()){

injectDefinition((String) inject.getValue(), def, tilesContext);

}

}

}

}

return def;

}

private void injectDefinition(String fromName, Definition to, TilesRequestContext cxt) {

assert null != fromName : "Definition not found " + fromName;

Definition from = getDefinition(fromName, cxt);

if (null != from) {

if (null != from.getLocalAttributeNames()) {

for (String attrName : from.getLocalAttributeNames()) {

to.putAttribute(attrName, from.getLocalAttribute(attrName), true);

}

}

}

}

}public class FinnTilesContainerFactory extends BasicTilesContainerFactory {

...

@Override

protected UnresolvingLocaleDefinitionsFactory instantiateDefinitionsFactory(TilesApplicationContext applicationContext, TilesRequestContextFactory contextFactory, LocaleResolver resolver) {

return new FinnUnresolvingLocaleDefinitionsFactoryImpl();

}

...

}When the Composite pattern is superior

Conclusion

1. Tiles-3

2. Composite pattern

3. Decorator pattern

4. Spring Web

5. Integrating Tiles and Spring

6. Initial discussion regarding Tiles definition delegation[Gone]

7. Spring 3.2 with Tiles-3 :: Tiles-3 support